Is it ok to mention the war yet?

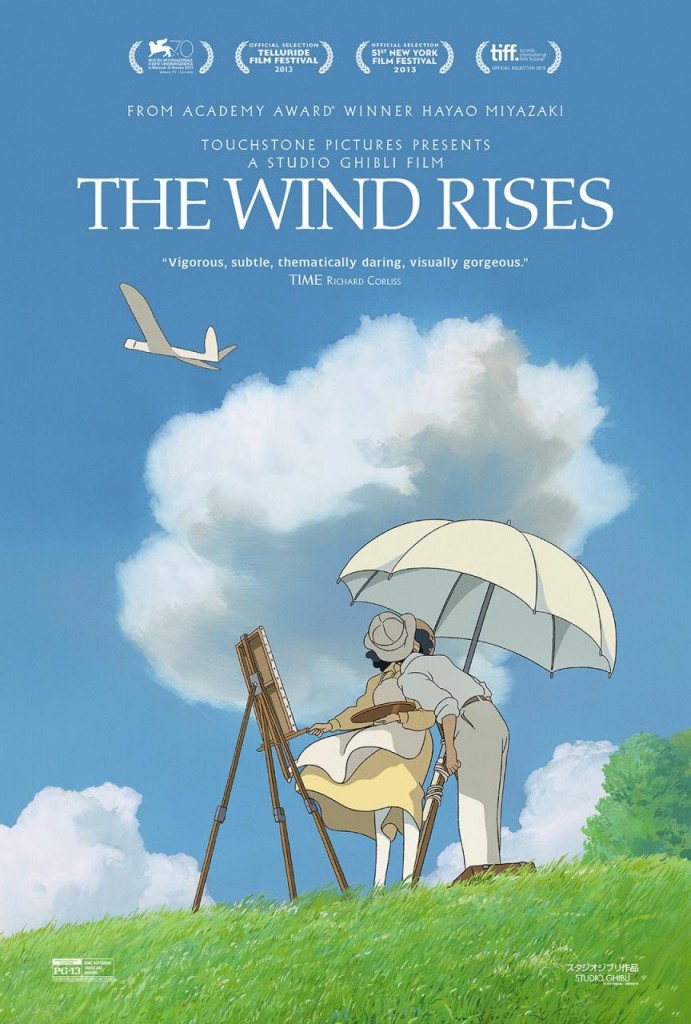

Every story has a side untold. Hayao Miyazaki’s last film, ‘The Wind Rises’ offers a rare and beautiful glimpse into a time and place that is very rarely portrayed on screen, especially in Western cinemas. Said to be the Studio Ghibli director’s last film, ‘The Wind Rises’ contrasts a stunning array of beautiful animation alongside a controversial glimpse into Japanese life and ambition leading up to World War II.

Based on the life of Jiro Jorikoshi as he grows from a boy who dreams of building planes into a Mitsubishi aircraft designer, the film has as its backdrop life in Japan from the twenties, depicting the natural disasters such as the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, through the economic deprivations and panic that took hold of the country in the thirties. Throughout there’s a sense of cultural embarrassment in the mentality of the characters as Japan lopes behind the West in terms of technology and modernisation, which drives a spirit of ambition and determination to overcome any impediments to modernisation.

It’s in this context that the building of Jiro’s plane takes its importance. It is not simply about the plane. It is about Japan growing up, of catching up with the rest of the world, of moving away from the past, and it’s fascinating to watch and beautifully depicted.

Unusual for a Miyazaki film, as fans of ‘Spirited Away’ and ‘Howl’s Moving Castle’ might find, ‘The Wind Rises’ is down to earth. There’s no witch casting spells or turning people into pigs. However, the very real and fact-based nature of the film is delivered in a manner that make the art of engineering into a magic in and of itself. We see the wonder in Jiro’s mind as his imaginings and fantastical dreams help us to discover just how wonderful the world of planes actually is. For anyone who played with Lego or Mechano growing up, Jiro’s enduring enthusiasm for planes and engineering is easy to relate to and if you leave the cinema wanting to dig out that old slide ruler and change your major to engineering, well, just don’t say you weren’t warned.

However, while it’s easy to become lost in watching Jiro and his happy but overworked aero engineering pals spend their days and nights creating beautiful planes, the fact is that these beautiful objects of dreams are in reality being made for the purpose of war and destruction, and this is an

Jiro’s labour of love is not a passenger plane, but a Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter plane, the plane used in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and by Japanese Kamikaze pilots. Moreover, it was built, in part, by Korean slave labourers. These points are not addressed in the film and their notable absence does tend to make an argument for the white washing of the impact of Japanese militarism. While the film does touch on how sad it is for the engineers who must make planes to carry bombs instead of passengers, it does tend to avoid a deeper involvement with the issues of Jiro’s involvement with this side of the war.important point picked up on by many critics.

Is this enough to write off the film and declare it “an intense session of propaganda”, as a fellow cinema-goer was overheard saying as we exited the cinema? Probably not. Articles online talk about how it’s inexcusable to create a homage to a man who designed killing machines. However, these go too far, and forget an important aspect to this issue. This film is about a man who wants to create beautiful planes, created by a man who wants to create beautiful films. And while Miyazaki was perhaps lax in turning his lens’ gaze away from the darker aspects of Japanese military drive, this film is not a homage to war. Far from it. It’s a homage to beauty and effort that goes into creating something beautiful.

– Words by Alice Macfarlan